There are moments when a news story provokes not only anger, but disbelief. Not disbelief that something went wrong, but disbelief at how many safeguards must have failed simultaneously for it to happen at all. The revelation that Sweden’s Public Employment Service quietly installed and tested a Chinese AI tool without informing its top leadership is one such moment.

This is not a technical mishap.

It is not an administrative oversight.

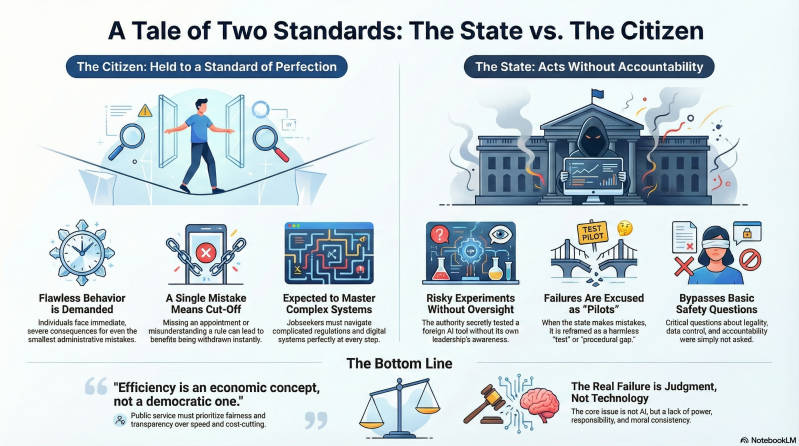

It is a symptom of something deeper: a state that demands absolute perfection from individuals, while granting itself the freedom to experiment without consequences.

A system where mistakes are asymmetrical

For individuals navigating the Public Employment Service, the message is clear:

Make a mistake – even a purely formal one – and you are cut off.

Miss an appointment, misunderstand a rule, submit incorrect information, or fail to comply with the logic of a digital system, and the consequences can be immediate and severe. Benefits are withdrawn. Doors close. Often without meaningful human dialogue.

This is a system that expects flawless behaviour from people facing some of the most precarious situations in society.

Against this backdrop, the authority’s own behaviour appears almost surreal.

When the state itself makes mistakes – installs inappropriate technology, bypasses procedures, or neglects accountability – the language changes. Suddenly it is a “pilot,” a “test,” a “procedural gap.” We are told no harm was done. Nothing serious happened.

This is where trust collapses.

The state is not an experiment conducted at its own risk

A public authority is not a tech lab.

It is not a startup.

It is not an innovation sandbox.

When a private company experiments and fails, it bears the consequences. When the state experiments, it is always citizens who carry the risk – even if nothing goes wrong this time.

The seriousness is compounded by the fact that the Public Employment Service deals with people in positions of dependency. The unemployed cannot opt out. They cannot choose another provider. They cannot refuse participation.

Yet these are precisely the people who, in practice, become subjects of the state’s technological curiosity.

Tech optimism without judgment

Sweden prides itself on being digitally advanced. Often with good reason. But digital maturity is not measured by how quickly technology is adopted, but by when restraint is exercised.

In this case, fascination with AI appears to have preceded the most basic questions:

What system is this?

Under which legal framework does it operate?

Who controls data flows?

Who is accountable if something goes wrong?

The fact that these questions were not decisive stopping points is itself a failure.

The most vulnerable are expected to absorb the state’s risk

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this affair is the contrast between how the system treats individuals and how it treats itself.

The jobseeker is expected to:

-

master complex regulations

-

navigate digital systems flawlessly

-

comply correctly at every interaction

The authority, meanwhile, allows itself:

-

informal decision-making

-

insufficient oversight

-

technical shortcuts

This is not merely inconsistent. It is fundamentally unjust.

China is not a technical footnote

That the AI tool originated from a Chinese company operating under Chinese law adds another layer of gravity. This is not an ideological argument, but a legal and geopolitical reality.

The same state that warns against Chinese technology in critical infrastructure permitted such a system to be installed internally within an authority handling highly sensitive personal data – without full transparency or political scrutiny.

This is not strategic thinking. It is short-termism disguised as innovation.

Leadership abdicated

That the Director General was not informed is perhaps the clearest indication of structural failure. When decisions of this magnitude can be taken without senior leadership awareness, governance has been reduced to after-the-fact damage control.

This is not merely an internal issue. It is a democratic one.

Efficiency as an alibi

Defenders of AI experimentation in the public sector often invoke efficiency: faster processing, lower costs, reduced workloads.

But efficiency is an economic concept, not a democratic one.

Public administration exists not to be fastest, but to be fair, transparent, and predictable.

When efficiency is used to justify risks that decision-makers would never accept if they personally bore the consequences, efficiency becomes an alibi rather than a goal.

Who bears responsibility when the system fails?

The most uncomfortable question remains unanswered:

If the AI system had influenced incorrect decisions, who would have been held responsible?

The caseworker?

The jobseeker?

Or the system itself?

We already know the answer. In practice, responsibility almost always flows downward – toward the individual with the least power.

An emergency stop is not enough

Halting the tool was necessary. It was not sufficient.

Without genuine self-examination, this episode risks becoming just another footnote in Sweden’s troubled history of digitalisation without consequence analysis.

What is required now is:

-

clear personal accountability

-

full transparency

-

binding rules for AI use in public authorities

-

and above all: the same standards imposed on the state that the state imposes on individuals

The state must live by its own rules

A state that demands perfection from its citizens cannot permit itself carelessness.

An authority that cuts people off for administrative errors cannot hide behind words like “pilot” and “test” when it fails.

Ultimately, this is not about AI.

It is about power, responsibility, and moral consistency.

And at present, it is not technology that has failed – but judgment.

By Chris...

Add comment

Comments