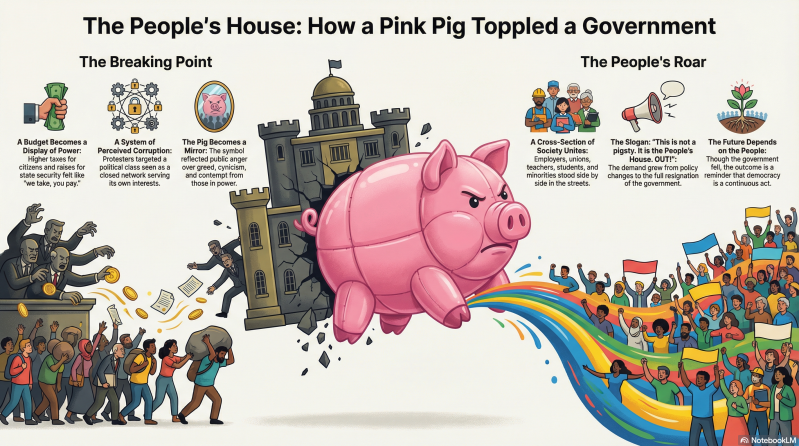

It began as a joke — or perhaps as art. A gigantic pink polystyrene pig, placed directly in front of Bulgaria’s National Assembly. An absurd object in the cityscape. But symbols have a strange ability to outgrow their creators. Within days, the pig became something else: a mirror. A confession. A roar given physical form.

Families took selfies beside it. Young people recorded videos. QR codes spread across the cobblestones. “Don’t feed the pig.” This was no longer a political message in the traditional sense — it was a popular language. A way of saying what so many had felt for so long but never truly managed to express: enough is enough.

When Emily Yordanova, 24, says, “This is the Bulgarian politician who is stealing from Bulgaria,” it is not an insult. It is a diagnosis. And when she adds, “We want a better life, better work and better politicians,” she puts her finger on something far bigger than a budget line. She gives voice to a generational longing for a normal European life — not luxury, not excess, just fair rules of the game.

When the Boil Finally Breaks

Bulgaria is no novice when it comes to protests. Since the fall of communism in the early 1990s, governments have come and gone, often amid allegations of corruption, clientelism, and abuse of power. Time and again, outrage has flared — and then faded. People went home. The system remained.

This time, it did not.

What triggered the protests was, on paper, “just” a budget: higher taxes for ordinary people and higher salaries for parts of the state security apparatus. But in a country where many are already struggling to make ends meet, it was perceived as something else entirely — a display of power. A message that said: we take, you pay.

It struck a deeper nerve. Behind the numbers lay a feeling built up over decades: that the state no longer exists for its citizens, but for a closed network of political and economic power brokers. When the threat of having even less in one’s pocket became tangible, so did the anger.

A Cross-Section of Society

What was most striking about the protests was not only their size, but who took part. Employers’ associations and trade unions. Teachers and students. Minorities and majorities. Roma leaders on stage. People who rarely stand side by side.

This was not an ideological demonstration. It was a cross-section of Bulgaria.

And it surprised everyone — including the organizers. Three times in three weeks, tens of thousands gathered in Sofia, and the movement spread to towns and cities across the country. There was no single party color, no obvious leader. Just one shared demand: resign.

When the demands grew from “withdraw the budget” to “the government must go,” it became clear that a point of no return had been crossed.

The Political Life of a Pig

The pink pig was initially intended as a kind of piggy bank — a reminder of where taxpayers’ money was going. But symbols live lives of their own. Suddenly, it became an icon. A physical manifestation of everything people experienced as greed, cynicism, and contempt from above.

Stickers appeared across Sofia. QR codes led to protest petitions. Children pointed. Tourists asked questions. And the politicians… they were forced to see it every day, right in front of their own house.

That was when the slogan gained its full force:

This is not a pigsty. It is the People’s House. OUT.

It was not directed only at a government, but at an entire way of understanding power. At its core, the protests were not about a pig — they were about who actually owns the state.

The Architects of Power

At the center of the anger were not only the outgoing government, but two names that surfaced again and again: Boyko Borissov and Delyan Peevski.

Borissov, the veteran — the symbol of a system that has outlived itself. Peevski, the more shadowy figure — former media mogul, politician, sanctioned by the United States in 2021 for corruption, yet still one of the most powerful individuals in the country.

For many Bulgarians, Peevski is not merely a politician, but an entire system embodied in a single person. A personification of what they perceive as a parallel power structure, where compromising material, the prosecution service, and economic interests are woven together into an efficient instrument of control.

When opposition figures speak of “a move toward hard autocracy,” it is not rhetoric. It is a fear widely shared: that boundaries are constantly being pushed, that there is always another line to cross — and that it is crossed, again and again.

Voices From the Margins — No Longer Silent

One of the most powerful moments of the protests came when Marin Tihomirov, 37, a Roma leader from Sofia, took the stage. His words cut through every attempt at political varnish.

“For 30 years, I watched how Borissov and Peevski bought my parents like tomatoes in the market.”

It was not merely testimony. It was an admission of how systematic poverty is used as a political tool. How people are kept vulnerable so they remain purchasable, silent, controllable.

When the crowd responded with a roar of recognition, it became clear: this was no longer “someone else’s problem.” It belonged to everyone.

A Different Kind of Anger

Martin Bakardzhiev, a visual artist, described something many felt but struggled to articulate: “For the first time, I sensed there was a bit of anger.”

Not fatigue. Not resignation. Anger.

Anger at the sense that power is embedded everywhere. That there no longer seems to be a clear limit to what is acceptable. And that the future therefore feels both threatened and uncertain.

This is a dangerous point for a society — but also a necessary one. Anger can be destructive, but it can also be cleansing. It can force change where apathy only cements the status quo.

What Happens Now?

The government fell. But no one believes in miracles.

Bulgaria remains ranked among the most corrupt countries in the European Union. Trust in institutions is low. The opposition has been in power before — and failed to hold together.

Skepticism is widespread: will it really be different this time?

The brutally honest answer is: it depends on the people.

As Assen Vassilev put it: “It’s up to the people. We do not take it for granted.”

This was not a victory to be filed away. It was a reminder that democracy is not a condition, but a continuous act.

The People’s House

The pink pig will remain in memory long after it is removed from the street. Because it achieved what statistics, reports, and EU recommendations never managed to do: it gave anger a form that could not be ignored.

And the message was crystal clear.

Parliament is not a pigsty where power can be fattened without scrutiny. It is the People’s House. A loan, not a possession. A responsibility, not a privilege.

When the people say “OUT,” it is not populism. It is a line being drawn.

And this time, it was heard — far beyond Bulgaria’s borders.

By Chris...

Add comment

Comments