There are sentences that sound dramatic, almost exaggerated, until you realize they are true.

“Russia has already occupied Gotland once.”

It sounds like a provocation in our time. Like a frightening headline. Like a hypothetical scenario from a security-policy seminar. But it is not fiction. It is history. And perhaps that is exactly why it is also about the future.

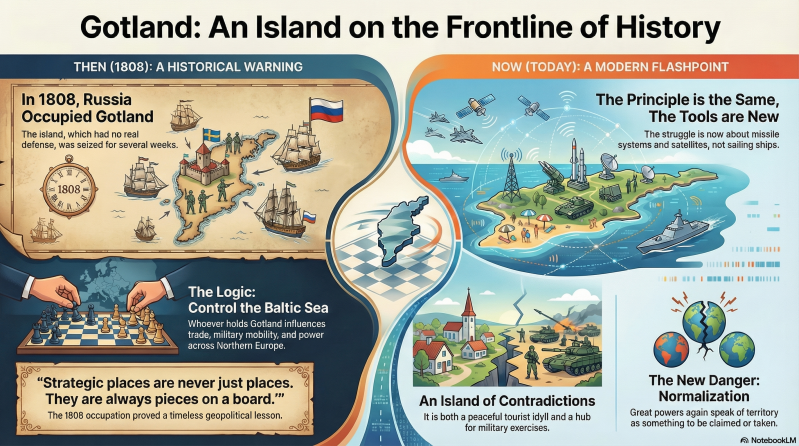

In 1808, Russian troops landed on Gotland. Not with bombs, not with missiles, not with cyberattacks – but with boats, muskets, and orders. The island had no real defense. There were no radar stations, no NATO aircraft in the air, no press conferences about “tensions in the Baltic Sea.” Just a simple fact: Gotland was suddenly no longer Swedish.

It lasted only a few weeks. But it was enough to show something that is still true two hundred years later: strategic places are never just places. They are always pieces on a board.

When the unthinkable has already happened

We live in a time when we often say: “That can’t happen.”

Russia can’t invade.

The United States can’t take territory.

Great powers can’t behave like empires anymore.

But history has an uncomfortable habit of whispering something else. It says: It has already happened. Many times. In many places. Under many flags.

When Russian troops landed on Gotland in 1808, it was not madness. It was logic. Gotland controls the Baltic Sea. Whoever controls the Baltic influences trade, military mobility, and political power across Northern Europe. That was true then. It is even more true now.

The difference is only the scale. Back then it was about sailing ships and artillery. Today it is about missile systems, satellites, and nuclear balance. But the principle is the same: power always seeks strategic nodes.

The language of great powers – the same melody, different words

There is something almost ironic in how similar great powers sound when they explain their actions.

Russia says:

“We must protect our security interests.”

The United States says:

“We must secure stability.”

China says:

“We must defend our territorial integrity.”

The words differ. The message is identical: We do what benefits us.

When American leaders talk about “owning” Greenland – whether half-jokingly or not – something dangerous happens. Not because Greenland will become American tomorrow, but because the idea becomes normalized. Territory once again becomes something that can be negotiated, claimed, taken.

And once that idea is released, it does not stop in the Arctic. It applies everywhere. In Taiwan. In Ukraine. In the Baltics. On Gotland.

Gotland as a mirror of our time

Gotland today is a concentration of our era’s contradictions.

On one hand:

An idyll. Holidays. Roses, limestone cliffs, the medieval walls of Visby.

On the other:

Radar systems. Military exercises. Strategic briefings. NATO planning.

It is as if the island lives in two worlds at once. One looks back toward history and summer calm. The other looks straight into the conflicts of the future.

It is no coincidence that Gotland is being fortified. It is not hysteria. It is not paranoia. It is an acknowledgment of an uncomfortable truth: the island is too important to be left to chance.

From neutrality to necessity

For a long time, Sweden lived by the idea of neutrality – not only as policy, but as identity. We were the country outside the blocs. The one that believed in dialogue over confrontation, in tradition over power politics.

But the world around us has changed faster than our self-image.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, one illusion collapsed. When China threatens Taiwan, another cracks. When the United States begins to speak in terms of spheres of influence, a third begins to crumble.

Suddenly small nations face a brutal reality:

Traditions no longer protect anyone.

Alliances do. Relevance does. Strategic value does.

Gotland is therefore not just a defense project. It is an existential awakening.

History that refuses to leave us alone

There is something deeply human in wanting to believe that history is over. That we have learned. That we now have institutions – the UN, international law, the EU, NATO – that prevent old patterns from returning.

But history is not a museum. It is an echo. It comes back in new forms, with new words, but driven by the same forces: fear, ambition, control.

When Russia took Gotland in 1808, it did so without great drama. No global opinion. No social media. No live-broadcast wars. Just a fact on the ground.

And that is precisely what makes it frightening. Because even today, things can happen quickly. Not always with explosions and headlines. Sometimes simply through decisions made far away, in rooms where the fate of small nations is discussed as items on an agenda.

The new danger: normalization

The greatest danger of our time is not the brutality of war.

It is the normalization of war.

When we grow accustomed to:

-

one country taking another

-

one people being displaced

-

one border being erased

…without the world stopping in shock, something breaks at a deeper level.

When great powers begin to speak openly about territory as something to “own,” “take,” or “claim,” we return to a world we believed was buried under the ruins of the Second World War.

In this context, Gotland becomes more than an island.

It becomes a symbol of the question:

Are small nations still subjects in the world – or merely objects?

A future that demands new honesty

There is no point in demonizing individual countries. Russia is not unique in its logic. The United States is not different. China is not an exception.

The difference is not in the desire for power – all great powers share that.

The difference is in how openly we dare to acknowledge it.

Perhaps it is time for a new kind of honesty in international politics. One where we stop pretending the world is governed by ideals, when in practice it is governed by interests.

For small countries like Sweden, this does not mean becoming cynical.

But it does mean becoming realistic without becoming resigned.

Gotland cannot be defended with romanticism.

But it can be defended with clarity.

Final words – the island that already knows

Gotland has already seen this once.

It knows how quickly “it can’t happen” can become “it happened.”

In 1808, it was Russian soldiers marching into Visby.

Today, it is security analyses marching into our consciousness.

The difference is that this time we cannot say we did not know.

We cannot say it came as a surprise.

History has already given us the answer key.

The question is not whether Gotland is important.

It always has been.

The question is whether we are ready to live in a world where even the obvious –

like the right to your own country –

is no longer obvious.

And perhaps it is precisely there, in that uncomfortable realization,

that the real struggle of our time begins.

By Chris...

Add comment

Comments