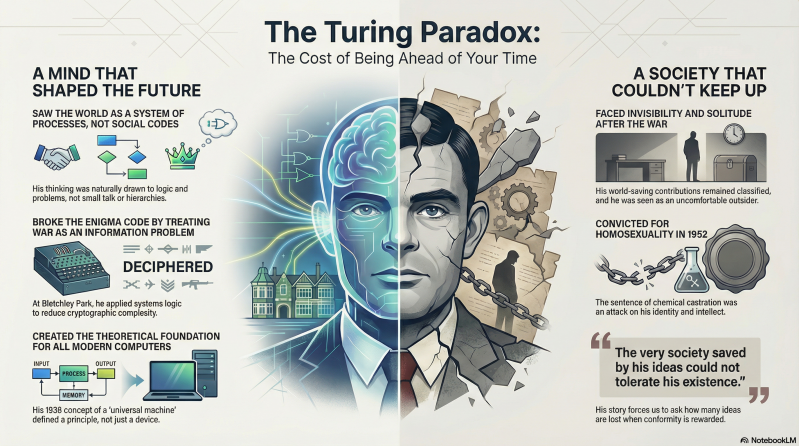

There are people who are born into their time. And then there are people who are born ahead of it. Alan Turing belonged to the latter category. Not because he sought to be revolutionary, but because his way of thinking simply refused to stay within the boundaries of his era. He saw the world as a system long before “systems thinking” had a name. And precisely for that reason, the world came to treat him as a problem.

This is not merely an essay about a mathematician. It is an essay about how societies respond to those who think too clearly, too deeply, and too early.

Seeing the world as process

Alan Turing did not experience the world as stories or traditions. He experienced it as processes. Events followed one another according to rules—not necessarily moral or social ones, but logical ones. For him, this was not a cold worldview. On the contrary, it was a way of understanding existence.

From an early age, he struggled with social codes. Small talk made little sense. Hierarchies held no interest. But problems—real problems—pulled him in with magnetic force. He could disappear into mathematical reasoning for hours, days even, so deeply that the outside world faded away.

Today we might speak of neurodiversity. At the time, people spoke of eccentricity.

Yet it was precisely this ability—to shut out noise—that made him extraordinary.

When thinking becomes dangerous

In 1936, Turing formulated an idea that, in hindsight, seems almost obvious, yet at the time was nearly incomprehensible: that any computable problem could be solved by a universal machine, provided the problem could be described in sufficiently clear steps.

This was not engineering. It was philosophy, mathematics, and logic fused into one. A thought about thinking itself.

In practice, he created the theoretical foundation for all future computers—before a single modern computer had been built. He did not define a device, but a principle. And principles are more dangerous than machines, because they outlive their creators.

Societies rarely reward those who change foundations. Often, they do not even notice them—until much later.

War as a system failure

When the Second World War broke out, Britain did not primarily need more soldiers. It needed thinkers. People who could see war not as chaos, but as an information problem.

Bletchley Park became a gathering place for such minds. There sat Alan Turing, not with weapons, but with paper, logic, and machines. The Enigma code was not evil in his eyes. It was complex. And complexity can be reduced.

By combining mathematics, statistics, and machine logic, Turing helped break one of the most advanced cryptographic systems of the war. The result was that the Allies could read enemy communications in near real time.

What is remarkable is not merely that he succeeded. It is how he thought. He did not rely on intuition. He relied on systems.

Today, we apply the same mindset in AI, cybersecurity, and data analysis. Back then, it was an existential gamble.

After victory: the true solitude

When the war ended, the world moved on. Turing did not. His work remained classified. His contributions invisible. He had saved lives in silence—and the silence continued.

This is a recurring pattern in history: those who carry societies through crises often have no place in peacetime. They do not fit. They are too sharp-edged. Too uncomfortable. Too difficult to place on a form.

Turing turned his attention instead to an even greater question: intelligence.

Can a machine think—and what does that say about us?

When Turing asked in 1950 whether machines could think, it was not about replacing humans. It was about understanding them. By attempting to create intelligence, we are forced to define what intelligence actually is.

His famous test was never really about machines. It was about perception. About the boundary between what we are and what we experience.

Today, as AI systems write texts, analyze emotions, and create art, Turing’s question feels more relevant than ever. Not because machines have become human—but because we are beginning to realize how much of our own thinking is already mechanical.

A society unable to tolerate the truth

At the same time, Alan Turing lived in a society that considered his sexuality a crime. When he was convicted in 1952 for homosexuality, it was not merely a legal punishment. It was a signal: you do not belong.

The sentence—chemical castration—was not only physical. It was an attack on his identity, his clarity, his concentration. For a man whose entire life depended on intellectual precision, it was devastating.

Two years later, he was dead.

This may be the most uncomfortable aspect of Turing’s story: that the very society saved by his ideas could not tolerate his existence.

What his life tells us about ourselves

Alan Turing is not merely a historical figure. He is a mirror. His life confronts us with questions we still struggle to answer:

How do we treat those who do not fit in?

How much creativity is lost when conformity is rewarded?

How many ideas die because their carriers are deemed inconvenient?

In a time when innovation is praised in words but constrained in practice, Turing reminds us that true renewal almost always comes from the margins.

A legacy that continues to work

Today, Turing appears on banknotes, in textbooks, and in tributes. But that is not where his true legacy lives. It lives in every algorithm that makes a decision. In every system that analyzes patterns. In every AI that forces us to ask: what does it really mean to be human?

His life teaches us that intelligence is not always socially smooth. That truth is not always comfortable. And that the future is often shaped by people their own time cannot understand.

Alan Turing died in 1954.

But his way of thinking lives on—as a silent engine of our digital world.

And perhaps that is the most fitting form of justice he could have received.

By Chris...